I’ve been fascinated with the invisible world and the transformative properties of sourdough for a long time. I am reposting this post from 3 years ago, because it sets up what is to come.

In 2018 I spent a week with Karl from The Sourdough Library, who has taken a sample of my sourdough starter back the library in Belgium, where there is collection of 91…( yes we are number 91) and he has sent the other sample to Marco Gobbetti, who I met in September, from the university of Bari, to be analysed.

It was 45 days before the full yeast and lactic acid bacteria identification and analysis was complete and this feature is one that shows how fascinated I have been and perhaps give an indication of just how excited I am to have the lactic acid bacteria and yeast strains identified.

The invisible world revealed.

A Close Look at my Starter – September 2014

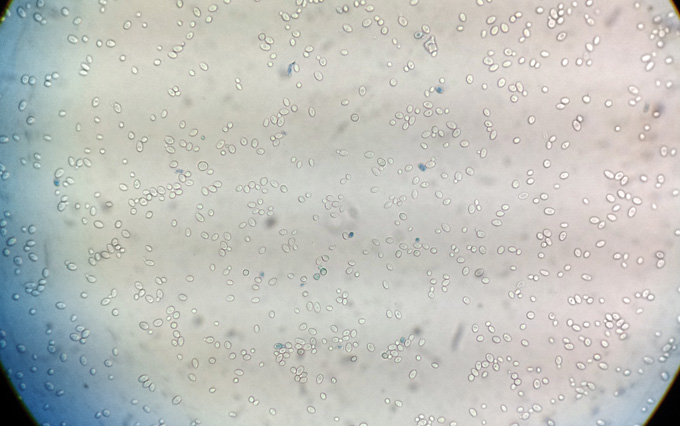

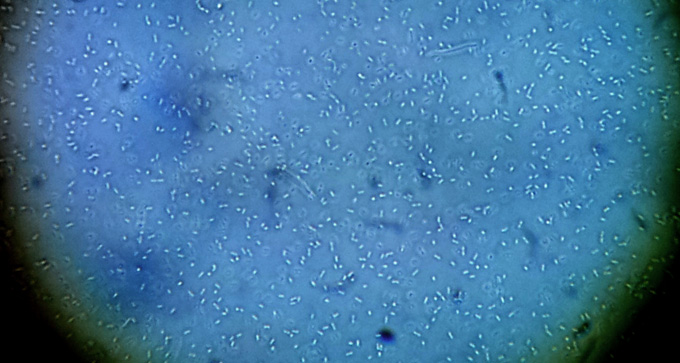

When I am teaching sourdough bread making on the course here, I often refer to my starter as a sourdough cultures. It’s a good name that reflects a little of what is going on, as sourdough is a complex ecosystem containing multiple species of yeast and lactic acid producing bacteria. Despite having had a close and somewhat intimate working relationship with my starter for more years than I can remember I had never actually see my starter close up I was in 2014 lucky enough to be invited to Lalemand, the UK’s largest yeast manufacturing factory in the UK and I was thrilled when they offered to take a look at my starter and analyse it in the laboratory. Seeing my starter under the microscope was almost as exciting as opening my stocking on Christmas day. The technician dropped some of my starter into a solution and placed it under the microscope….and there they were. My yeasts and my bacteria. Wild sourdough yeasts don’t live alone in a monoculture. Unlike baker’s yeast dormant cells of bacteria float through the air all around us and hang about in wheat waiting for a place to call home. When they find wheat they begin to reproduce and their digestive process is “fermentation.” To see these microorganisms close up with my own eyes and seeing both the yeast and bacteria side by side was magical

The yeast and the bacteria have a mutually beneficial symbiotic partnership sharing all the available nutrients form the flour. Rather than compete for food they cooperatively protect their ecosystem from other uninvited bacteria. The yeasts are tiny oval shaped one-celled fungi and when they have access to oxygen aerobic fermentation produces carbon dioxide gas (CO2.) These are the bubbles that you see in the bread dough which is what makes your bread rise. I’d just fed the starter the night before on the basis that I wanted it to be as lively as possible. So I was even more fascinated to see them move. The yeast’s made their way around the petri dish like footballers running around a pitch in a random manner.

When they are aerobic then they are at their most active. Of course, when the yeast ferments in the absence of oxygen (anaerobic fermentation) it produces alcohol and slows down, which is why when you see a sourdough culture that has been left to ferment for a while without being aerated or fed develops a thin layer of alcohol (called hooch) on the surface. It is this alcohol combined with lactic acid that provides an additional flavour dimension. I’ve been baking with sourdough since I was a little girl and I never tire of it. The idea that there is an eco system in a pot that behaves differently according to the conditions that it lives in fascinates me. The Sourdough bacteria are much tinier than the yeast and are lactic acid-producing bacteria (lactobacilli) (these can also be found in numerous other fermented foods and it is these bacteria that produce the unique flavours and textures. They are also responsible for the increase the nutritional value of sourdough bread, through digesting the indigestible bits of flour.

The bacteria eat carbohydrates, fats and proteins and then produce acids, most notably lactic acid and to a lesser extent acetic acid (vinegar). The pH of sourdough changes according to the stage of fermentation it is at but in general it has a pH 3.5 – 5. It is this acidity that keeps out of pathogenic microorganisms such as botulism bacteria, E. coli bacteria and spoilage fungi as it is unable reproduce in an environment with a pH below 4.6. Nevertheless I was shocked as the technician took a swab and labelled up the petri dish as E-coli. I had never considered that my sourdough might have bad bacteria in it. “You’ll have to wait three or four days until we know if it has any E-coli or other nasty’s in it.” he said with a grin.

I have to admit I really wasn’t expecting this aspect to be tested, but was greatly relived to have the results back which gave my starter the all clear. I was confident that the Lactic acid bacteria had protected the ecosystem so the and prevented pathogenic microbes from invading the sourdough ecosystem and upsetting the balance. It is these same organic acids that keep sourdough bread mould-free far longer than bread made with baker’s yeast.. All in all it was fascinating to see my sourdough ecosystems is healthy and resilient, especially as this one is an heirloom sourdough starter that has been passed down for many generations. Thank you to Lallemand, especially Martin Perling, for so generously testing and photographing my starter for me.

A Full list of Bread Making Courses in the UK and Ireland

A Full list of Bread Making Courses in the UK and Ireland

Is the ultimate flavor of the bread vary with the feeding, storing and general cultivation of the starter? For instance, when I make sourdough daily, I feed the starter daily and leave out at room temp. When I take a a break for couple of days, I store it in the refer without feeding it. What is the best way of bringing the activity back (temperature and how long of a fermentation before use)?

Also, when increasing sourdough batch baking size, what is the best way to build volume (quantity) in the starter to account for the increase in loaves.

The ultimate flavour of the bread can vary due to many different aspects. When dealing with sourdough, it can vary according to the type of process used, whether ambient or retarded. It could also vary according to the flour that you use for the starter. The starter base is a very interesting place to start because the way in which you feed your starter – the timings, the temperature, and the type of flour – will impact the balance of the bacteria, and this in turn impacts the amount of sourness and the depth of flavour at the base of your recipe. So, it’s complex, but the starter is the base. Dr Kimbell

Hello Vanessa!!

I’ve just received your sourdough starter from Bakery Bits and I have a question.

Should I mix the whole sourdough of the pot with flour and water or just a little bit?

Thanks!!!

The depends on what you are trying to do.. refresh or make a leaven… ?

Thanks for that. I’ve often wondered what’s going on in my starter and how it appears to change over time – fascinating!